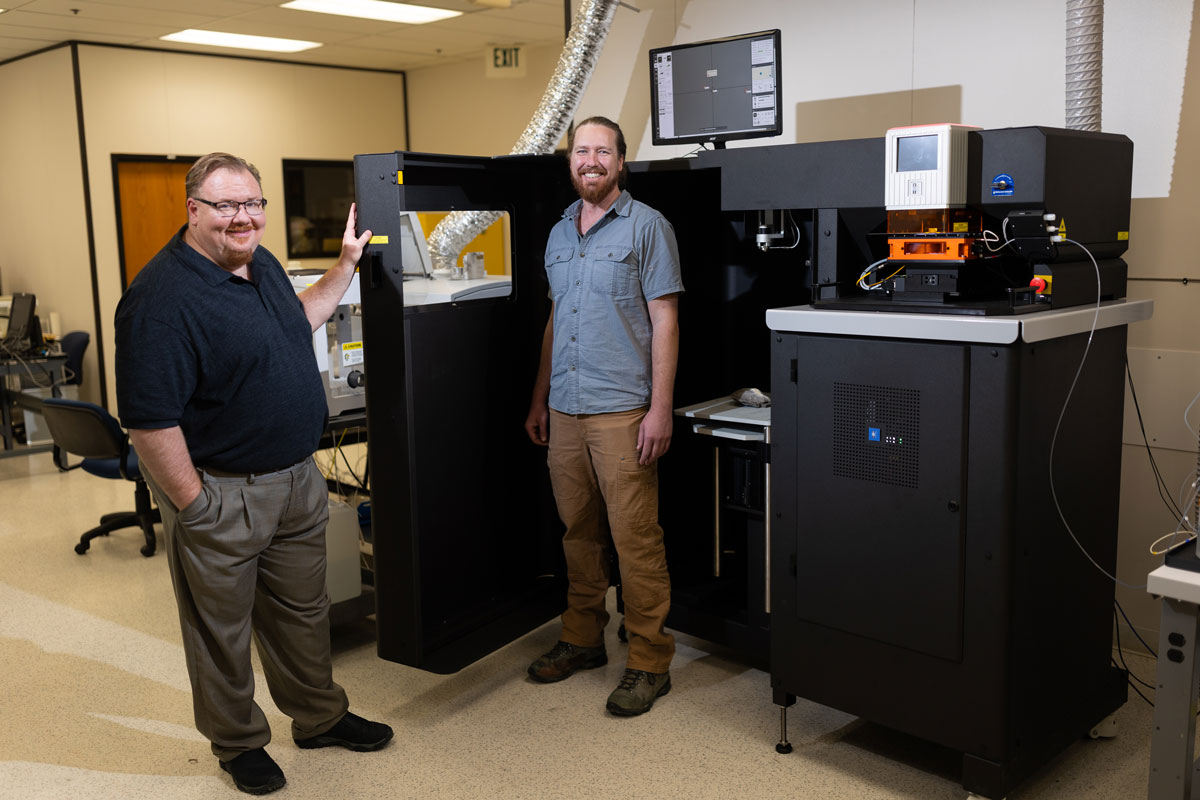

Idaho State University’s advanced laser ablation machine is opening new doors for research across many fields by revealing details at a microscopic level. One of only a few systems like it in the world, ISU’s custom-built instrument allows researchers to study artifacts in a minimally invasive way. Here’s a look at what this powerful tool has helped uncover in its first year on campus.

Tiny Marks, Big Discoveries

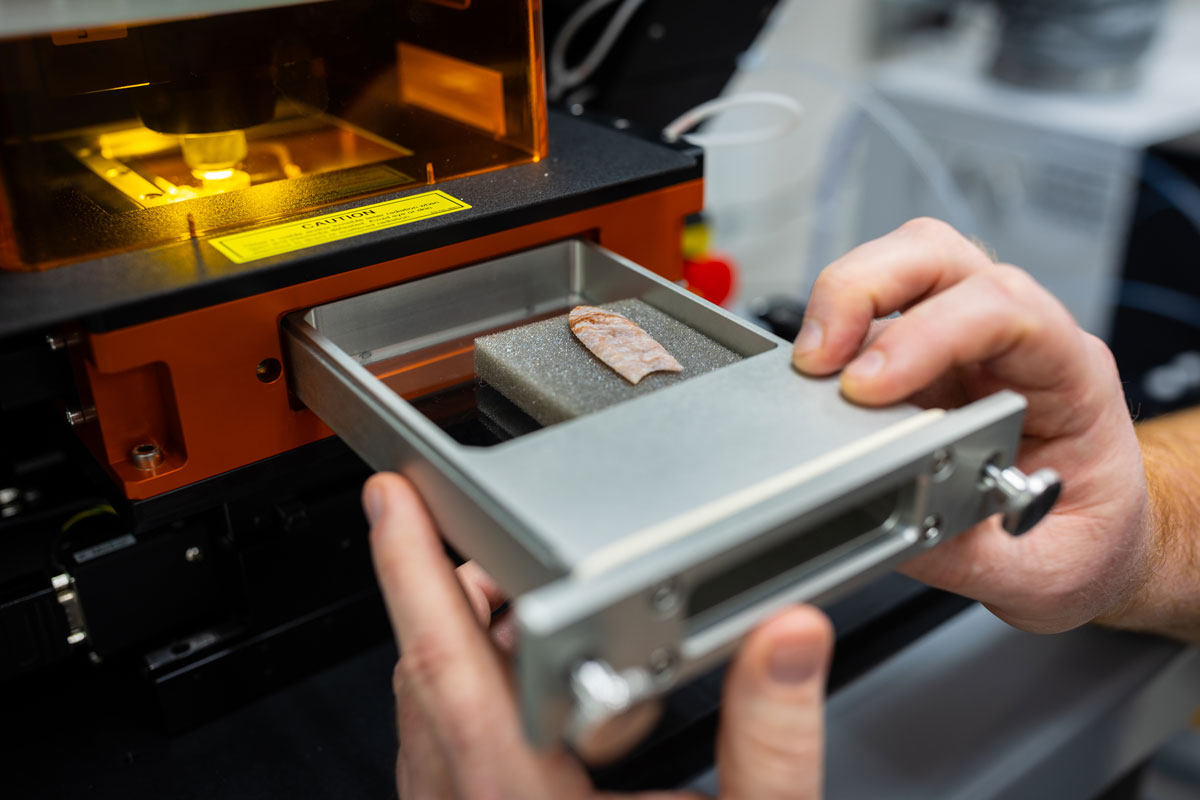

Anthropology professor Andy Speer, Ph.D. leads research with the laser ablation machine. His team is exploring how small a laser ablation spot can be while still producing useful data. They have experimented with samples less than half the width of a human hair to minimize the visible impact on artifacts.

“It’s a game-changer for museums or private collectors who don’t want to risk damaging their items,” said Speer, who presented these findings at the Society for American Archaeology Meetings in Denver this spring.

This technology could encourage more museums to allow artifact testing, opening valuable new research opportunities.

Ancient Trade

Speer is collaborating with Dr. Rachel A. Horowitz of Washington State University to analyze Mayan household tools from Guatemala. They’re testing whether the tools were made with local or imported materials, offering insights into ancient trade routes and power structures.

“The collaboration with CAMAS at ISU is instrumental to the chert sourcing project in western Belize, in the Maya area,” Horowitz says. “Since chert sourcing is not as common as it is for other types of stone raw material types, working with someone who has sourced chert in regions with similar types of geology makes the process much easier.”

In the long-term, Horowitz explains that the geochemical sourcing of chert will provide researchers with detailed information about the lifeways of past Maya peoples.

Geochronology

ISU assistant professor of geology Kurt Sundell, Ph.D., and graduate student Cheyenne Bartelt are using zircon dating and radiometric techniques to study the age of ancient rock formations in Wyoming’s Greater Green River Basin.

To unlock what happened in the Green River Basin and ancient Lake Gosiute, Sundell and Bartelt will head out to six different locations in the basin to measure the order and position of various rock layers and collect rock samples which will then be analyzed in the laser ablation machine.

Bartelt explains that detrital zircons act like chemical time capsules, helping geologists trace the origins and history of ancient rocks by revealing when and how they formed.

“What excites me most about geologic research,” Bartelt says, “is the ability to tell Earth’s stories from millions of years ago using a few grains of sand.”

Human Migration

Speer and his team are exploring how laser ablation can be used to study human migration by analyzing chemical signatures in bones and teeth. “Our bones remodel throughout our life, while our teeth retain chemical signatures from early development,” Speer explains. By comparing both, researchers can track where a person was born and how they moved throughout their life.

While established methods exist, they’re costly and time-consuming. “We’re testing whether our machine can do it more efficiently,” Speer says.

Such techniques could one day assist forensic investigators in identifying the geographic origins of unidentified human remains.

The First Farmers

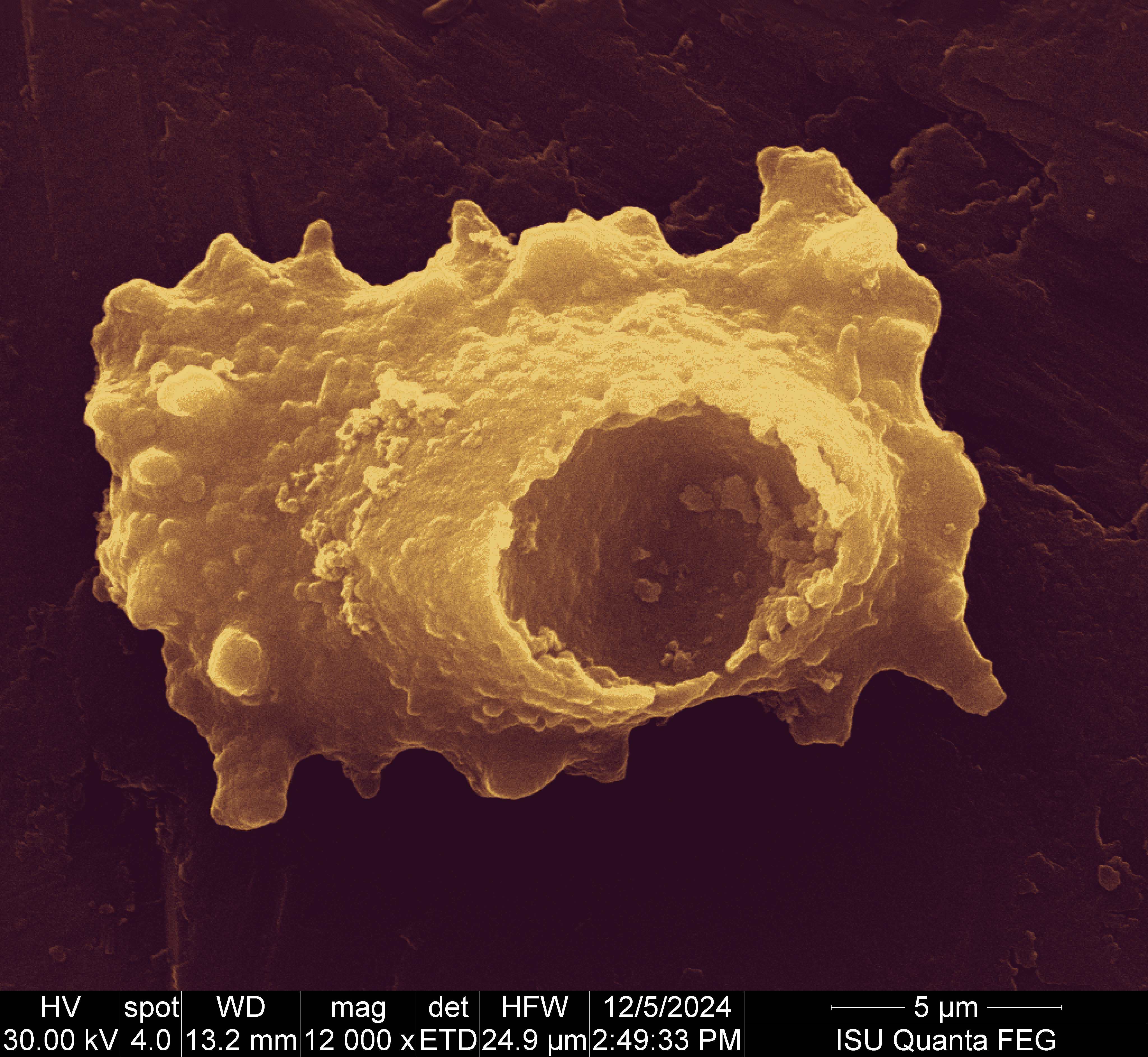

Ph.D. student Rebecca Hazard is using laser ablation to study the early cultivation of bananas in Fiji. Working with anthropology professor John Dudgeon, Ph.D., she analyzes trace elements in phytoliths—microscopic silica structures in plants—to uncover when and how domesticated bananas were introduced.

“Bananas are important in Fiji,” Hazard explains, “because they were introduced by people, appearing in the archaeological record only as a result of human presence and activity.”

Early findings suggest bananas were grown inland earlier than once thought. “This is significant,” she says, “because if we continue to find evidence for early inland colonization and horticulture in Fiji, it could have implications for other sites in the Western Pacific that were colonized by the same people, the Lapita.”

Hazard’s research is supported by a National Science Foundation Dissertation Improvement Grant. She also manages a banana plant growth lab on ISU’s campus.

Widespread Interest

The lab draws researchers from across the country. Paul Thacker, Ph.D., of Wake Forest University in North Carolina is teaming with Speer to examine the patina layers of 17,000–24,000-year-old stone tools from Portugal’s Azinheira Ridge. They aim to determine how environmental exposure affects sourcing data by analyzing the weathered exterior and freshly flaked interior of the tools.

Dionysios Stamatis, a Ph.D. student from the University of Iowa, is analyzing uranium levels in cave formations to study the impacts of ancient human or industrial activity.

Closer to home, Speer is gathering geological materials from Oregon, Nevada, Utah, and Idaho to analyze Clovis-period tool caches including the Simon Cache in Idaho and the Busse Cache in Kansas. Speer hopes that the machine’s ability to take non-damaging samples will allow them to sample more artifacts and gain more understanding about early tool-making and trade in North America.

Continued Discovery

Speer is currently seeking funding for a portable laser ablation system, which would allow researchers to capture samples on-location and in museum collections without transporting delicate or culturally sensitive materials, opening new possibilities for collaboration and access.

From anthropology to botany, geology to forensic science, ISU’s laser ablation lab is rapidly becoming a hub for interdisciplinary research.

“The instrument allows us to ask new questions and collaborate in ways we couldn’t before,” says Speer. “There’s incredible potential for crossover. Every time we work with someone from another field, we discover something new.”